For us in the Northern Hemisphere, March’s Vernal Equinox ushers in spring. Earth’s rotation around the sun makes our star appear to move north of the Equator. Our planet tilts on its axis, as the sun’s path across the sky shifts northward. Celebrations and traditions across the globe span from Cahokia in the US to Angkor Wat, Cambodia; to Chichen Itza, Mexico; to Iran to Stonehenge and beyond.

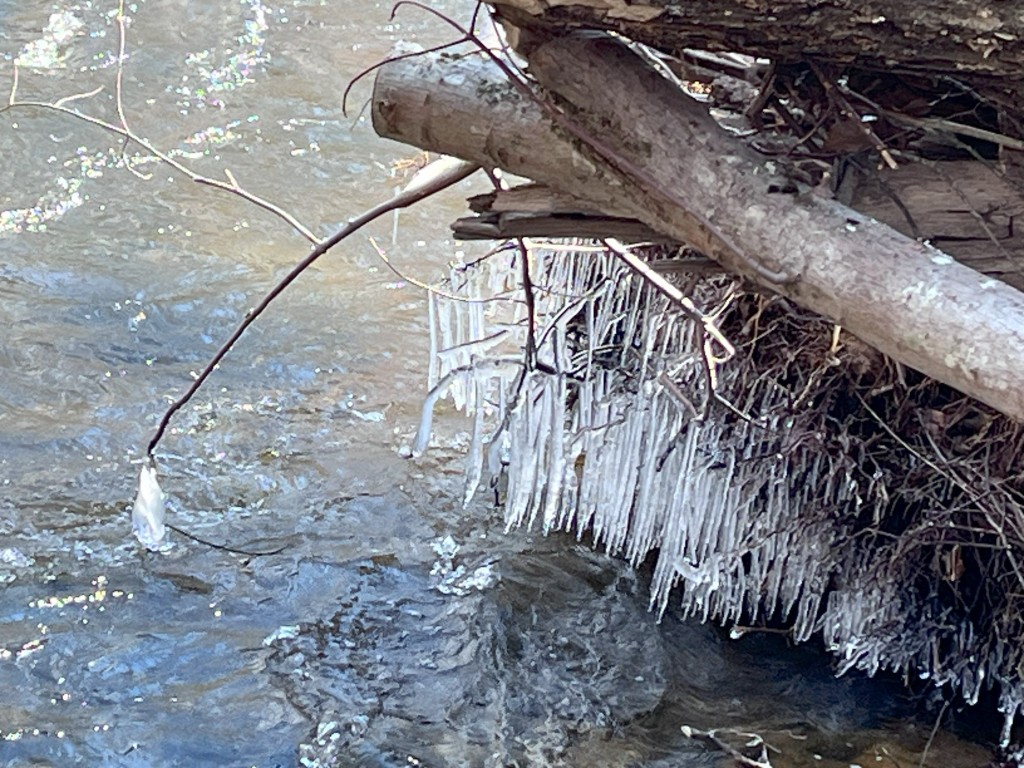

Weeks ago I walked with B. to the river flowing through the woods behind us, the water touched by late winter’s icy fingers (I can’t say the last of winter anymore, with climate change so deeply affecting all life).

Early March blooms signal spring: skunk cabbage – the incomparable, improbable flower – pokes out of the snow, actually generating its own warmth to attract pollinators…

… then follow snowdrops…

… and later, crocus – I first spied it through a window, in a forest lit by midafternoon sun. Eager for the next bulbs, I know they’ll come soon, thanks to the thoughtful planting of our home’s previous inhabitants: daffodils, then iris, later daylilies, blooms lasting into late spring.

Andromeda surprises, adorning the garden with fragrant sprays of delicate bell-like blossoms:

One rainy night a grey treefrog, the first this season, graced our back door.

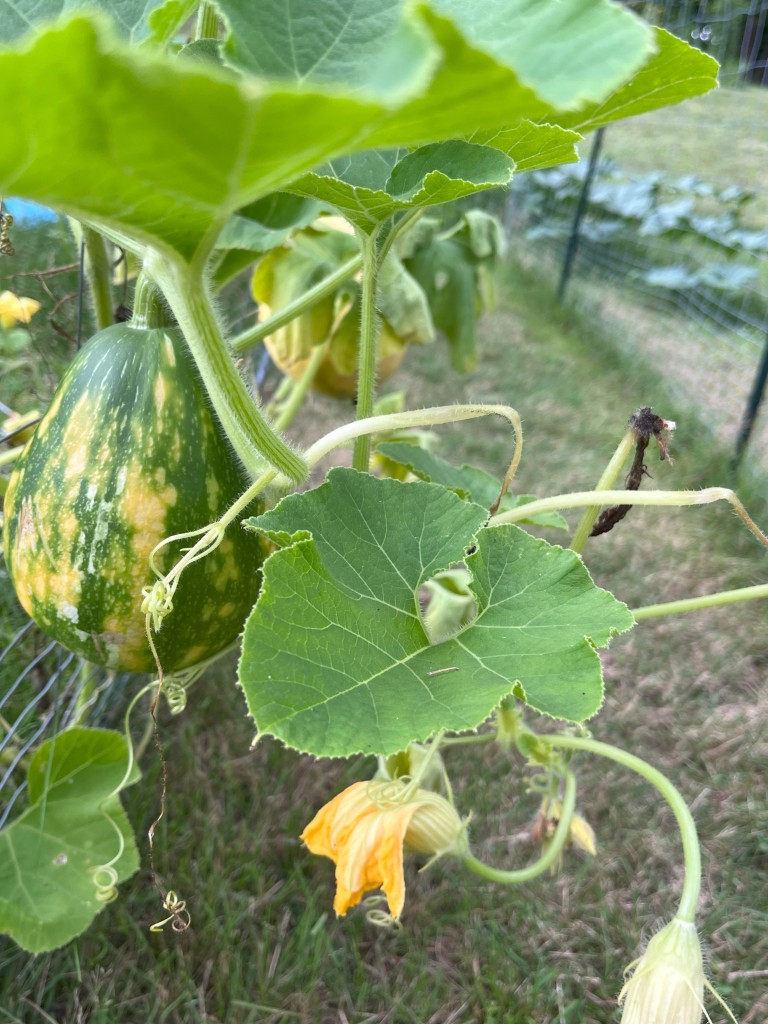

Joining the neighborhood in a flurry of activity, planning and planting seeds, flowers, fruits, and vegetables, we watch as songbirds return to the feeders one by one from their winter migratory grounds. Soon will arrive their babies, their parents nourished at least partly by our seed and suet, nests replenished by our yard clippings, spent blossoms and dead leaves.

This season’s warmer, longer days literally fuel this regeneration, as unfurling leaves and buds help shake off winter blues with energy, quickening with new life.

Happy Spring!